Everyone agrees that the way to literacy is to read, read, then read some more. But in this era of mental canapés, a brainy meal in current affairs is hard to find. With newspapers getting thinner and thinner before they succumb to the anorexia of no readers, and magazines getting fluffier and fluffier with lots of pictures interrupted by tiny bites of text, imagine my delight when I discovered a couple of meals for the price of a subscription, and a feast for the price of a book.

The Magazines

These two magazines specialize in words—weighty words—to feed your brain with delicious knowledge:

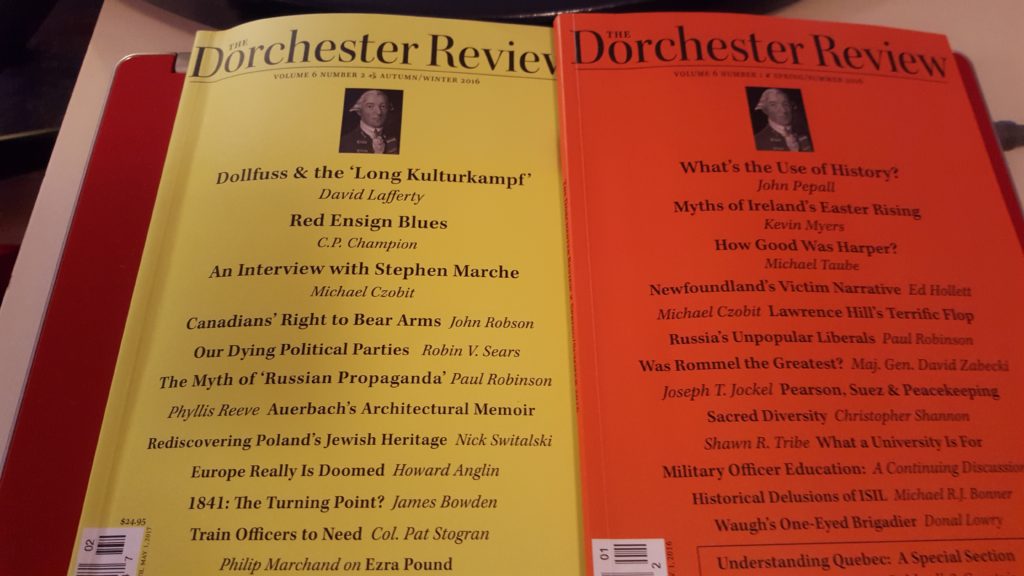

- The Dorchester Review, a historical and literary review published twice a year by the Foundation for Civic Literacy from its headquarters in Ottawa, ON

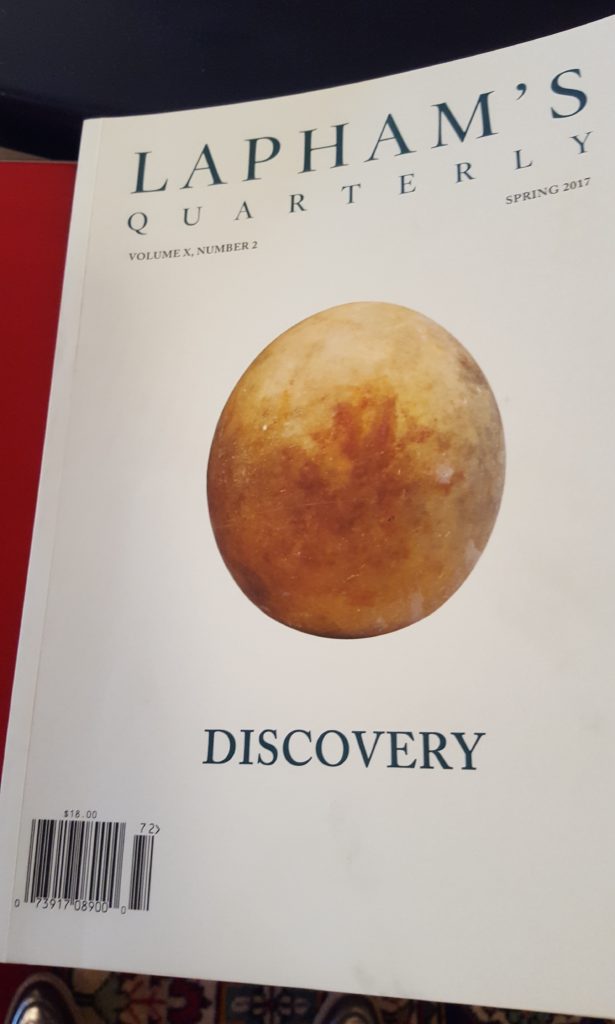

- Lapham’s Quarterly, edited by Lewis H. Lapham published four times a year by the American Agora Foundation from its headquarters in New York, NY

With one being Canadian and the other American, they span our North America continent to feed the few who still read historical, literary and political essays to challenge and enlighten ourselves.

The Dorchester Review

I discovered The Dorchester Review when Barbara Kay wrote about it in her column in the National Post and encouraged her readers to subscribe to this newly founded magazine. Her endorsement was seconded by David Frum, “Distinctly Canadian, thoroughly intelligent, and refreshingly non-left-wing”, and George Jonas. “The best first issue of any comparable periodical I have seen, here or elsewhere”. With three of the finest writers giving their imprimatur, I needed no more encouragement.

Teaching history – The Spring/Summer 2016 edition opens with a bang: “What’s the Use of History?” by John Pepall who makes the case that “History should not be the property of a few academics but for the general public”—music to the ears of someone who has been bemoaning the younger generations’ lack of historical knowledge. And our public schools and mainstream media abet this lack, teaching and presenting content as if anything before yesterday is so last century and, therefore, not worth knowing about or, even worse, knowing about only in the current postmodern context. “Post-modern theories are not there to be proved or falsified but to show people in the past quite cleverly but perhaps unconsciously, or was it deceitfully, doing something naughty.” The hubris of this prevalent attitude in academia is breathtaking in its venality and stupidity.

This is a ‘gotcha’ approach to teaching history, the very antithesis of teaching the story of civilization. “Good history paradoxically teaches both humility and confidence. Humility because what seems obvious to us now did not seem obvious to people in the past, to the most decent and intelligent people… And confidence because much of the past is a record of misery and muddle and yet we have come through.” Good history should feed our interest in how we came to understand what benefits and what undermines peoples’ lives and countries’ development. So even when we repeat our ancestors’ mistakes, perhaps we’ll inch forward in civilizing the world. But we certainly won’t do it if we don’t appreciate the shoulders on which we stand.

Focusing on Canada – And that is just the first of many provocative essays—with a focus on Canada but an embrace that encompasses the world—in the first two editions. I join the editor in his “appeal to subscribers and readers to renew your efforts to persuade friends and acquaintances—and even better, enemies—to subscribe to the magazine.” If you like to think and discuss and argue, you’ll enjoy every hour of weighty reading its writers create—and contribute to its continuation.

Lapham’s Quarterly

Now to our American cousin. My introduction to Lewis Lapham was as editor of Harper’s Magazine, a position he held from 1976 to 2006. I found his editorials and columns well written and thought-provoking, even when I dramatically disagreed with his point of view. But the magazine, begun in 1850 to “explore the issues that drive our national (i.e., US) conversation” via “long-form narrative journalism and essays”, began to drift too far leftward—as so many of the leading magazines did in the 1990s and 2000s—and I didn’t renew my subscription. I had heard about Lapham’s new venture, but never had the time or inclination to track it down. Then in the bookstore in

Port Royal in West Van a few weeks ago, there it was, staring me in the face as I was paying for my books.

Discovery – The Spring 2017 edition is Discovery—“The unknown is the largest need of the intellect.” Emily Dickenson, 1876—with an introduction by Lapham of humans’ endless exploration of everything and the “near-infinite expanse of human ignorance” still to be explored. The essays are grouped into three actions—To Strive, To Seek, To Find—with authors writing across the centuries: Seneca in 60 AD, Galileo in 1615, Coleridge & Wordsworth in 1802, Einstein in 1918, Ross Anderson in 2014, to name a few. Some are read by many, some by their fellow specialists, and some by very few. But all make the reader tingle with anticipation as the reading begins.

To Strive, To Seek, To Find – To Strive has Ross Anderson on Elon Musk’s reaching up to the stars because “I think there is a strong humanitarian argument for making life interplanetary,” Musk says, “in order to safeguard the existence of humanity in case something catastrophic were to happen.” To Seek has Burkhard Bilger reaching down to the centre of the earth to chronicle the extreme cavers and their exploration of the Chevé system, some 85,000 feet deep, in the Sierra de Judrez mountains of Oaxaca, Mexico. To Find has Francis Hodgson Burnett reaching inside the imagination, “Then she slipped through it, and shut it behind her, and stood with her back against it, looking about her and breathing quite fast with excitement and wonder and delight. She was standing inside the secret garden.” And this is just the tiniest appetizer of what’s in store for the reader. Do subscribe.

The Book

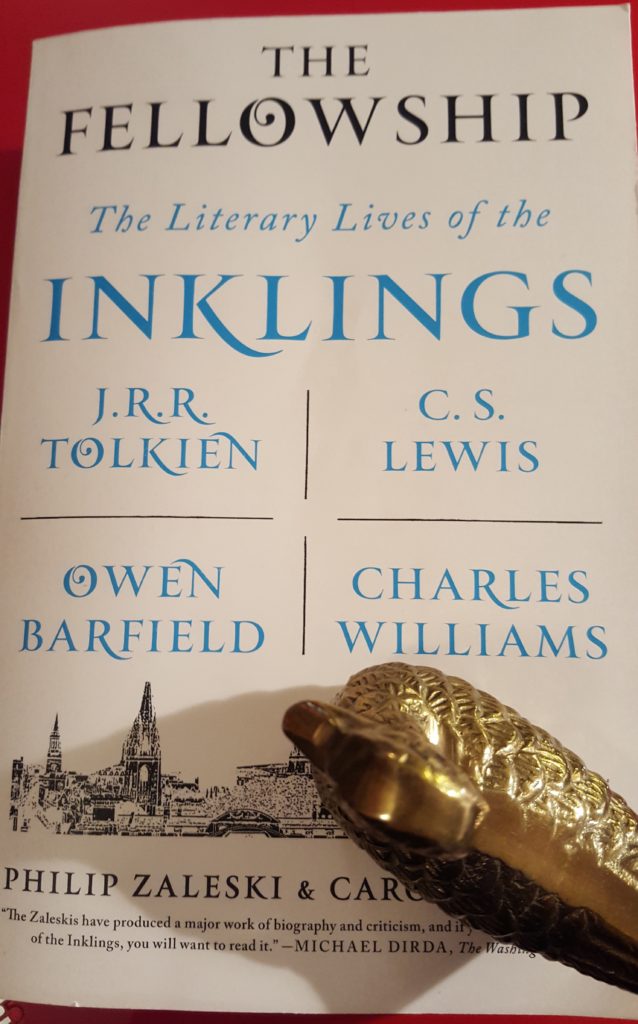

Those are the magazines; now for the book: The Fellowship, The Literary Lives of the Inklings: J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Owen Barfield, Charles Williams by Philip & Carol Zaleski. The first two are well known—Tolkien for The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy, and Lewis for The Chronicles of Narnia, especially The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, and Mere Christianity—but ‘eccentric geniuses’ Barfield and Williams not so much in North America.

The Inklings – This foursome was the core of the Inklings, a group of Oxford writers and intellectuals whose work “…bears the special stamp of Christian faith blended with pagan beauty, of fantastic stories grounded in moral realism,” as described by the Zaleskis. They met every Thursday evening in Lewis’s quarters in Magdalen College and Tuesday morning in The Eagle and Child (“Bird and Baby”) pub in Oxford where they ate and drank copiously while verbally jousting about all and sundry in the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s. (Oh, what I would have given to be at one of these sessions! But on not quite as learned a scale, my family did our share of verbally jousting around the dinner table on subjects great and small.)

Tolkien & Lewis – Tolkien was always a devout Roman Catholic, but Lewis rejected religion in his youth and only came to a deep and abiding belief in Christianity in his maturity. Lewis’s father neatly sums up this age-old path: “He is young and he will learn in time that a man has not absolutely solved the riddle of the heavens above and the earth beneath and the waters under the earth at twenty.” The characteristic that attracted me most to Lewis was his catholic taste in reading.

“Lewis exhorts us to become the kind of generous readers he himself was: capable of enjoying works of vastly different genres, idioms, and periods, quick to appreciate but slow to declare a work unfit; distrusting one’s negative reactions as indications of bias; and extending the franchise of aesthetic judgment to everyone who loves to read,” the Zaleskis write.

Great literature – But there is a hierarchy in reading, as all readers soon discover. “In reading great literature,” Lewis writes, “I become a thousand men and yet remain myself. Like the night sky in the Greek poem, I see with myriad eyes, but it is still I who see. Here, as in worship, in love, in moral action, and in knowing, I transcend myself, and am never more myself when I do.”

The Inklings inspire admiration and emulation. I can think of no more fascinating group I’d want to be a member of—a group of readers and thinkers who discuss literature and ideas, and enjoy the companionship and criticism that come from dining copiously at the table of human curiosity.

Deep and thoughtful reading is always a delight. It demands our full attention and (in my case) access to paper and pen to write down queries on the subject at hand. Thank you for suggesting some great ways to read with intention. I would also add to this list Robert Lanza’s, Biocentrism: Rethinking Time, Space, Consciousness and the Illusion of Death.

Thanks for the suggestion, Gabriole, and it’s on my books-to-check-out list. BMP