In 2021, I explored two regions of the world that I knew little about—the Balkans and North Africa—and came away with a deeper knowledge of the ‘barbarians’ and an even deeper appreciation of the Allies’ victory in WWII. We take far too much for granted in our Western world, and too many have become fatheaded with their grossly overestimated self-worth. So it is salutary for one’s mental health to be reminded of the bounty we inherited from our ancestors in the last millennium and in the last century. Christopher Hitchens, in his introduction to Rebecca West’s book, is perfect in his admonition: “‘The enormous condescension of posterity’ was the magnificent phrase employed by E.P. Thompson to remind us that we must never belittle the past popular struggles and victories (as well as defeats) that we are inclined to take for granted.”

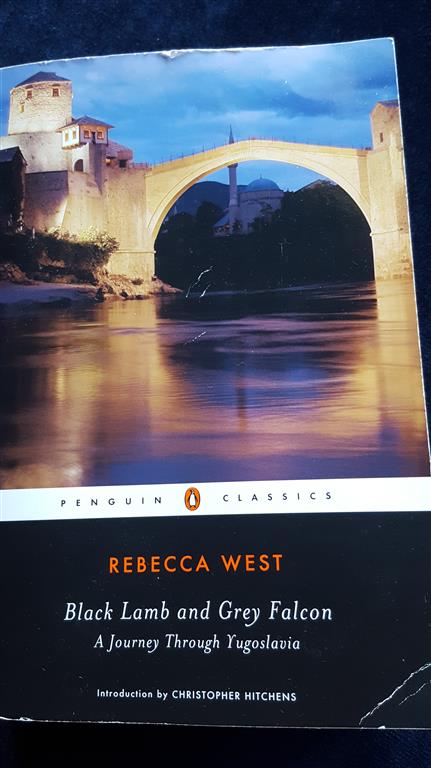

Black Lamb and Grey Falcon

by Rebecca West

Reading her ‘Journey through Yugoslavia’ in our time of the Left’s war on the West is fitting because I share Hitchens’ belief “that (Rebecca) West was one of those people, necessary in every epoch, who understands that there are things worth fighting for, and dying for, and killing for” and “that certain kinds of life are a version of death.” It is good to read West’s affirmation, “It was good to take up one’s courage again, which had been laid aside so long, and to feel how comfortably it fitted into the hand.”

So I began on the journey. And the journey became personal when it dawned on me that, on my mother’s side, my roots are barbarian—the Slavs who roamed across the wild steppes of eastern Europe and spilled down into the Balkans. West’s journey began when she heard on the news that the King of Yugoslavia had been assassinated, engendering a feeling of dread that this was an omen of impending catastrophe. It was 1934. The unconcern of many of her fellow Britons spoke to her of the root of ‘idiot’:

Idiocy is the female defect: intent on their private lives, women follow their fate through a darkness deep as that cast by malformed cells in the brain. It is no worse than the male defect, which is lunacy: they are so obsessed by public affairs that they see the world as by moonlight, which shows the outlines of every object but not the details indicative of their nature.

In other words, while the idiots gaze at their navels, the lunatics run rampant in the asylum!

West fell in love with the South Slavs—the Serbians, Croatians, Dalmatians, Herzegovinians, Bosnians, Macedonians & Montenegrins—when she traveled through their lands in 1937. In their church ceremonies, she witnessed “people with a unique sort of healthy intensity.” They argue passionately: “I find that this always happens when I try to interrupt Slavs who are quarreling. They draw all the energy out of the air by the passion of their debate, so that anything outside its orbit can only flutter trivially.”

Shades of talk around our kitchen table with all 13 of us joining in the fray, leaping from argument to argument and faction to faction—exhilarating for the tribe, bewildering for the outsider. West’s guide throughout her travels with her husband in what would be united into Yugoslavia, Constantine is a Serb by adoption only, but completely, and now a Government official who is passionate about trying to make Serbia work. In arguing with his intellectual friends, Constantine erupts, “My God, my God, how easy it is to be an intellectual in opposition to the man of action! He can always be so much cleverer, he can always pick out the little faults. But to make, that is more difficult.” Shades of socialists everywhere who create nothing and criticize everything.

The Madonna in the Pietà over the doorway is “as sorrowful as sorrow; her son is dead as death. There is here the fullest acceptance of tragedy, there is no refusal to recognize the essence of life, there is no attempt to pretend that the bitter is the sweet.”

West’s observation about the Ottoman Empire should give pause to the progressives’ virulent criticism of Western civilization. “The West has done much that is ill, it is vulgar and superficial and economically sadist; but it has not known that death in life which was suffered by the Christian provinces under the Ottoman Empire.” But the progressives, being historical idiots, will continue to shriek their complaints, I’m sure.

West loved the Slavs—their “intensely democratic” spirit; their “readiness to carry on a conversation forever, to stay up all night; in Dostoevsky’s continuous, unremitting spiritual excitement”; “their desire to know the whole”; in their “purse-pride which comes not from wealth but from poverty, in (their) conception of handsome spending as an inherently good thing, to be indulged in, like truthfulness, even against one’s economic interest”; their good looks and colourful, beautiful national dress.

Her journey across Yugoslavia brings West the devastating knowledge that the black lamb—the sacrifice—and the grey falcon—the appeaser—are accomplices.

This I had learned in Yugoslavia, which writes obscure things plain, which furnishes symbols for what the intellect has not yet formulated… There I had learned how infinitely disgusting in its practice was the belief that by shedding the blood of an animal one will be granted increase; that by making a gift of death one will receive the gift of life. There I had recognized that this belief was a vital part of me, because it is dear to the primitive mind, since it provided an easy answer to various perplexities, and the primitive mind is the foundation on which the modern mind is built.

As it was with the Slav surrender of Tsar Lazar to the Turks at the battle of Kosovo in 1389, so it was with Chamberlain’s appeasement of Hitler in 1938. “Again the grey falcon had flown from Jerusalem, and it was to be with the English as it was with the Christian Slavs; the nation was to have its throat cut as if it were a black lamb in the arms of a pagan priest.”

Lest we forget.

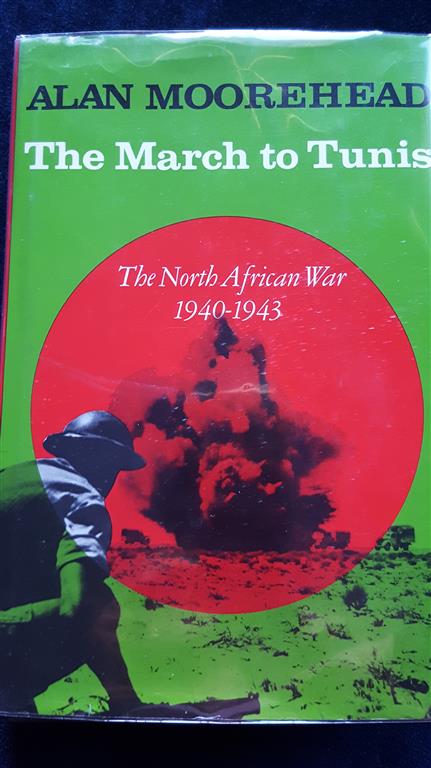

The March to Tunis: The North African War 1940-1943

by Alan Moorehead

Luckily for the English—and Western civilization—West’s dire forecast never came to pass because Winston Churchill, like his compatriot West, “was one of those people, necessary in every epoch, who understands that there are things worth fighting for, and dying for, and killing for” and “that certain kinds of life are a version of death.”

The events described in African Trilogy (the British title of this book) form part of one great historic canvas—the war in the desert during Hitler’s war—leading to the clearing of the Axis powers from the North African coast, and opening the Mediterranean to Allied shipping…”

An apt summary of Moorehead’s book by Field-Marshall Viscount Montgomery in the Foreword for the book. Montgomery was one of the three military commanders, along with Eisenhower & Alexander, who led the Allies to victory over the Axis in North Africa, with their chief adversary the Nazis’ Field Marshall Rommel and his Afrika Korps.

1940-1941. The history starts in “1940-1941: The Year of Wavell” when the British forces, led by Field-Marshall Viscount Wavell, were waging war against the Hitler’s Nazis & Mussolini’s Fascists. The desert is very much a player in the battles for good or ill. “But the morning I drove toward Mersa Matruh, looking for Force Headquarters, a khamseen was blowing, and that of course changed everything. The khamseen sandstorm, which blows more or less throughout the year, is in my experience the most hellish wind on earth,” writes Moorehead. The desert terrain & weather are adversaries to be survived along with the battles against the enemy troops.

Connected to Britain as Canada is, Moorehead’s observation about British rituals resonates. “It is never in London that you get a sense of Empire. It is here on the edges where they really do dress occasionally for dinner and cling pathetically to habits that were made in Eton and Piccadilly. It’s absurd, of course. And quite unusually stoical and brave.” I second the last sentence, stoically and bravely. His description of the ‘flying officers’—young, slim, handsome—is haunting.

Most of them were completely unanalytical…. Their response to almost everything—women, flying, drinking, working—was immediate, positive and direct. They ate and slept well. There was little subtlety and still less artistry about what they did and said and thought. They had no time for leisure, no opportunity for introspection. They made friends easily. And never again after the speed and excitement of this war would they lead the lives they were once designed to lead. They were no material for peace.

One lived there exactly and economically and straightly, depending greatly on one’s companions in a world that was all black or white, or perhaps death instead of living… Little things like an unexpected drink become great pleasures, and other things which one might have thought important become suddenly irrelevant or foolish. In a hunter’s or a killer’s world there are sleep and food and warmth and the chase and the memory of women and not much else. Emotions are reduced to anger and fear…tempered sometimes with a little gratitude… The soldier gives if he can and receives if he can’t. There is no other way to live. A pity this is apparent and imperative only in the neighbourhood of death.

1941-1942. This was The Year of Auchinleck, who replaced Wavell as the commander of the Allied troops in North Africa. He was a loner, had a wife but no children with the army “the ruling passion of his life. He had no interests outside the war.” This was a year of battles, but few successes, “with painful, agonizing slowness—the slowness that Lord Milne meant when he spoke of war as consisting of short periods of intense fear and long periods of intense boredom.”

The highlight in this long year of battle was the revival of ‘the spirit of the French soldier in the last war’.

…there was a touch of Verdun at Bir Hacheim. As the Guards had fought with stubborn discipline at Knightsbridge, so now the French fought with art and desperate comradeship and were gallant in their own way. All the bitter accusations against the French soldier after the fall of France were being denied and proved false under this little tricolour that kept hanging in the dusty folds on the ridge of Bir Hacheim. Wherever you went in the desert, you found the rest of the men of the Eighth Army full of glowing pride for the French.

But contrary to most Americans’ belief that the majority of troops doing the fighting were American, “it was very largely a British operation, and from the start of the Tunisian campaign to its finish (the final battle in this theatre of WWII) the Americans never amounted to more than one-quarter of the troops engaged. (This is not to say that the campaign would have been won without American troops and equipment.)” And most Britons believed that Northern Tunisia is flat desert, not the actual terrain of the battle that “was being fought in the mountains and the mud”, making progress tedious, difficult and slow. In fact, Moorehead points out “the fundamental inability of civilians to realize that war is a painfully long, slow process”, which leads to disenchantment when decisive victories don’t come swiftly.

And a final reminder about the men who fought and won the war for us.

It is useless to picture these men who were winning the war for you as immaculate and shining young heroes agog with enthusiasm for the Cause. They had seen too much dirt and filth for that. They hated the war. They knew it. And they were very realistic indeed about it… They wanted to win and get out of it—the sooner, the better…

The real degrading nature of war…can never be understood by anyone who hasn’t spent months in the trenches or in the air or at sea… Only a tiny proportion, one-fifth of the race perhaps, know what it is, and it is an experience that sets them apart from other people. If you find the men do not want to talk about the fighting or what they have done, it will be for this reason only—they want to forget it.