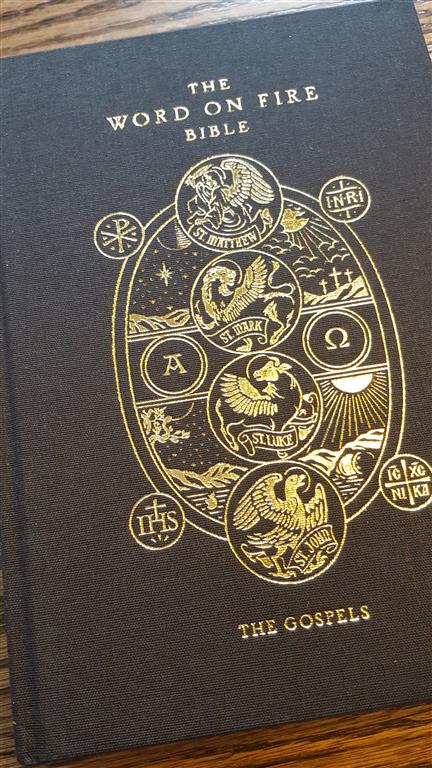

A book offer popped up on my email the other day. Nothing newsworthy about that, you say, as book offers appear daily, weekly, monthly in inboxes, especially those of readers of books and book reviews. But this one was offering an ancient book presented in a new and beautiful way—the WORDonFIRE Bible (Volume 1): The Gospels . Surrounding the timeless text is commentary by the Church Fathers, saints, mystics, Christian scholars and Bishop Robert Barron, its ‘author’, along with works of art and writing. The result is “A Cathedral in Print” to illuminate Catholic Christianity.

I’ve tried to read the Bible from beginning to end, but I get bogged down in the endless begats and my attention starts to wander. Then I drift away to other words in books, magazines and articles, and the Bible becomes buried on my bedside table. But this Bible promises a more inviting experience with its words and message illuminated by insightful commentary and beautiful pictures.

I look forward to hours of thoughtful reading—reading that will be enhanced by the following books about the Bible.

A Dialog

In 2013, I discovered a book Between Heaven and Hell, A Dialog Somewhere Beyond Death with John F. Kennedy, C.S. Lewis & Aldous Huxley by Peter Kreeft. The three of them died within hours of one another on November 22, 1963, and “All three believed, in different ways, that death was not the end of human life.” Kreeft imagined the conversation they might have if they met after death. They represented the three main versions of Christianity: orthodox – Lewis; humanistic – Kennedy; and mystical – Huxley. Their conversation is fascinating and ends with Lewis quoting his poem, “The Apologist’s Evening Prayer”:

From all my lame defeats and oh! much more

From all the victories I seemed to score;

From cleverness shot forth on Thy behalf

At which, while angels weep, the audience laugh;

From all my proofs of Thy divinity,

Thou, who wouldst give no sign, deliver me.

Thoughts are but coins. Let me not trust, instead

Of Thee, their thin-worn image of Thy head.

From all my thoughts, even from my thoughts of Thee,

O thou fair Silence, fall, and set me free.

Lord of the narrow gate and the needle’s eye,

Take from me all my trumpery lest I die.

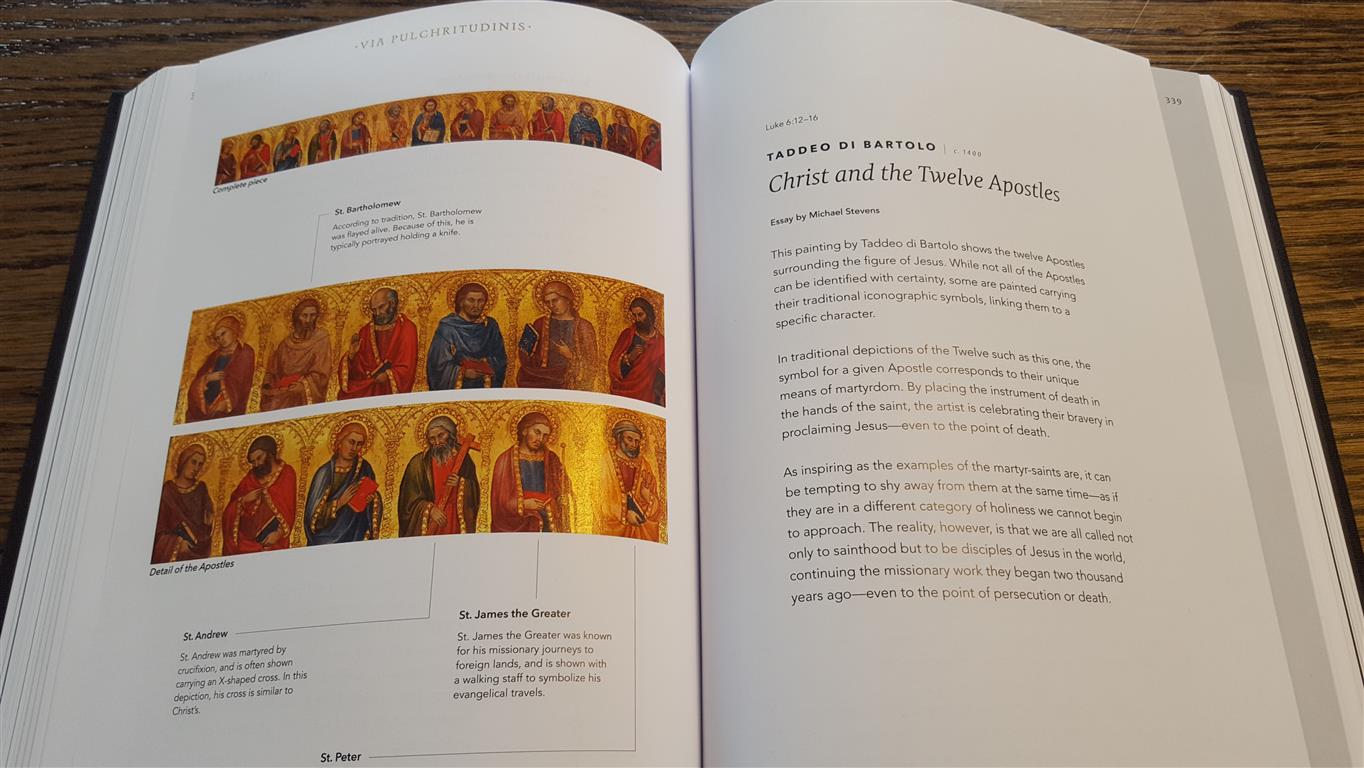

Christ and the Twelve Apostles by Taddeo di Bartolo

Christian apologetics by C.S. Lewis

Which brought me to read Mere Christianity by C.S. Lewis. I had loved Lewis’ writing since I’d read The Chronicles of Narnia to my boys many long years ago, but had only come to know of his Christian apologetics many long years later. When I learned of Mere Christianity, it headed my booklist for Christmas 2014, and then my reading list in January 2015. Its effect was profound, and I concur with Kathleen Norris in her Foreword in my edition when she writes, “Lewis betrays a deep faith in the power of human imagination to reveal the truth about our condition and bring us to hope.” And hope is the essential ingredient that we need to keep on going.

I must admit I was puzzled by Lewis’ choice of adjective. ‘Mere’ suggests something inconsequential, something unimportant, a bagatelle, as it were. But Lewis uses it in the sense of Christianity as a way of life, not as a philosophy or theology to discuss, to argue about how many angels can dance on the head of a pin, then to be put aside to get on with ‘real’ life. No, mere Christianity means imaginatively transforming our lives ‘in such a way that evil diminishes and good prevails’—a monumental task that must be approached daily, not in some overwhelming battle that once won, stays won. Because it is daily, it is humanly achievable; but because it is daily, it continues all the days of our lives.

To be a mere Christian is an immortal task. There are no ordinary people in the struggle to be good.

Virgin Mary & Jesus by Leonardo da Vinci

(The echo of Lewis’ Mere Christianity can be heard in W.G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn, a writer with a distinctly nonreligious approach to the search for meaning: “Perhaps we all lose our sense of reality to the precise degree to which we are engrossed in our own work, and perhaps that is why we see in the increasing complexity of our mental constructs a means for greater understanding, even while intuitively we know that we shall never be able to fathom the imponderables that govern our course through life.” Sebald is the human-centred pessimist, while Lewis is the God-centred optimist.)

The cultural point of view

A.N. Wilson, writer and journalist prominent in British literary circles, comes to the Bible from a cultural point of view with The Book of the People: How to read the Bible. He thinks an enlightened person must have the Bible on her bookshelf, easily available mentally and physically because Western culture is saturated in the Bible—Christianity in the New Testament, fed by Judaism in the Old Testament.

Wilson’s ‘guide’ starts with “why the Quest for the Historical Jesus, in which I have foolishly indulged in myself, is a dead end which can only lead nowhere”—a start that highly recommended the book to me. Then in the next six sections that make up the book, Wilson attempts to answer the question, “What sort of book is the Bible?” He explores the Torah, the sacred tenets of the Jews, written separately over many decades and centuries, in which God is a really different concept from the many gods & goddesses populating the many myths and religions of ancient peoples. He explores the Prophets, the Jewish Scriptures and the Gospels, uncovering their profound influence on Western civilization, as we traverse its journey from the ‘Garden of Eden’ to today’s ‘free’ societies, emulated & attacked. Externally & internally.

To Wilson, the Bible is “a work of the imagination…The act of creation was not finished when the first scribe wrote the words of Scripture on a piece of papyrus”; it had only just begun. He abhors equally the fundamentalists who insist on the literal truth of the Bible, and the secularists “who reject our religious heritage”. The Bible is the Living Word, constantly being reimagined every time it is read or heard by a human being.

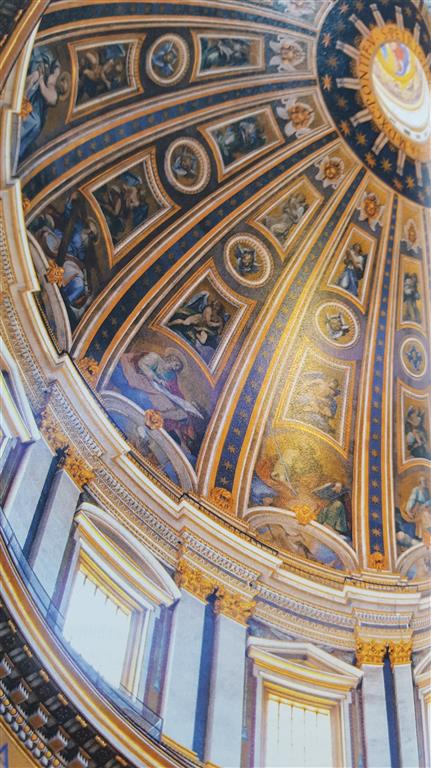

The Dome,

St. Peter’s Basilica

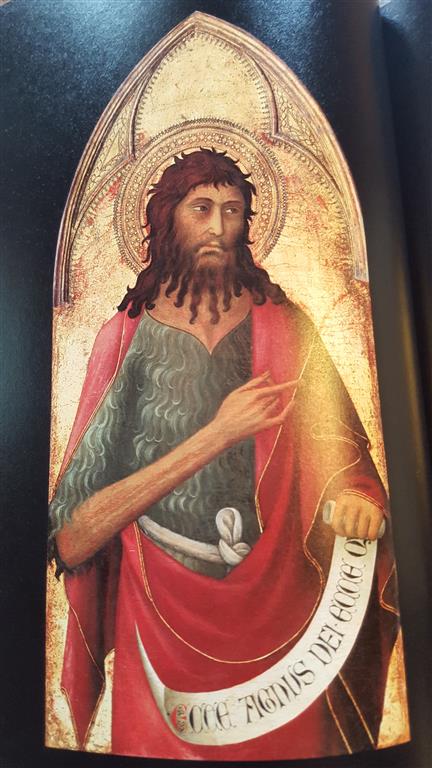

Saint John the Baptist by Lippo Memmi

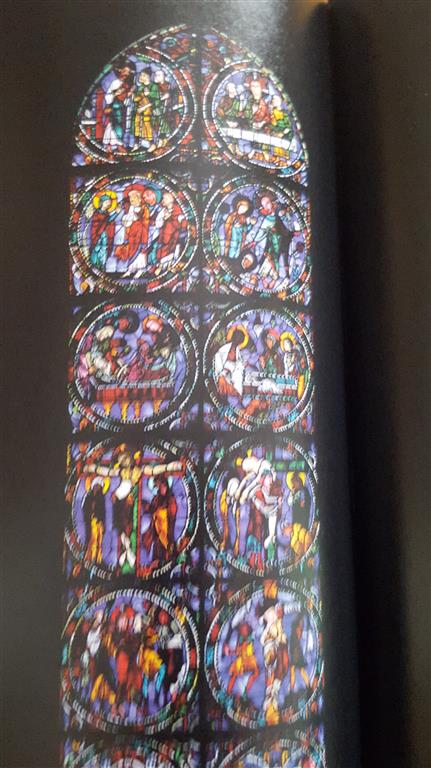

The Passion Window, Chartres Cathedral

The Screwtape Letters. The inscription at the beginning is apropos at any time, but especially so today amid the clamour of evil on the streets of cities across the USA:

“The devil…the prowde spirite…cannot endure to be mocked.” Thomas More

And for pride, Lewis nails it. Screwtape identifies the ideal candidates to lead the young man down the path to hell: “—rich, smart, superficially intellectual, and brightly sceptical about everything in the world. I gather they are even vaguely pacifist, not on moral grounds but from the ingrained habit of belittling anything that concerns the great mass of their fellow men and from a dash of purely fashionable and literary communism.”

Lewis takes the reader through the fall of man humourously and insightfully, wincing at our weaknesses, but taking heart from our capacity to overcome our temptations—partially, daily—to become a better person.

The Abolition of Man. Again, Lewis makes the case for universal values that is just as relevant today as it was when he wrote the book in 1944. That is the goal of the left—to abolish man’s soul and his inalienable right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness—and replace it with an identity.

The degeneration of education Lewis writes of in 1944 has relentlessly continued, producing ‘men without chests’—men without honour, men without dignity, men without values. “There have never been, and never will be, a radically new judgement of value in the history of the world.” From which flows, “An open mind, in questions that are not ultimate, is useful. But an open mind about the ultimate foundations either of Theoretical or of Practical Reason is idiocy.”

In their questioning of all values, today’s social-justice warriors are destroying all values, their own included. “When all that says ‘it is good’ has been debunked, what says ‘I want’ remains. And when that happens, “They are not men at all. Stepping outside the Tao, they have stepped into the void. Nor are their subjects necessarily unhappy men. They are not men at all: they are artefacts. Man’s final conquest has proved to be the abolition of Man.”

In a mere 81 pages, Lewis eloquently makes the case for men with chests—a case that needs to be on every syllabus in the Western world.

The Story of the World’s Most Influential Book

To start at the beginning again, I read A History of the Bible by John Barton last fall. In our increasingly liberal, progressive West where relativism dominates, counterintuitively, the churches that are growing are those of a more conservative bent where Scripture dominates. Their five principles for reading the Bible are:

- “We should read the Bible in the expectation that what we find there will be true.”

- “Scripture is to be read as relevant.”

- “Everything in the Bible is important and profound.”

- “Scripture is self-consistent.”

- “Scripture is meant to be read as congruent with the content of the Christian faith, with what the early Christians called ‘the rule of faith’.”

A contrast, indeed, with postmodernism where no firm foundation remains except that there is no firm foundation!

Judaic beginnings. To start at the historical beginning, “modern scholars tend to think that the eighth century—possibly the age also of Homer—is the earliest likely period” and the second century BCE the latest when the texts that make up what Christians call the Old Testament were written. According to Jewish tradition, the Old Testament—or Judaism’s Bible—is divided into three sections: the Law (torah); Prophets; and Writings, including Psalms, Proverbs and Chronicles. Most of the books were written in Biblical Hebrew, a Semitic language that is unrelated to European languages; Semitic languages were spoken all over the ancient Near East, as they are today. As noted, the Old Testament was not produced at one time, but is an anthology of books marked by diversity and complexity.

Christian beginnings. In contrast to the Old Testament written over centuries with an official tone, the New Testament “was written in less than a century, from the 50s to perhaps the 120s CE. It’s “the literature of a small sect…and in its origins unofficial, even experimental writing.” The New Testament was written mostly in ‘common’ Greek, a simplified version of classical Greek, which was understandable to all educated speakers. “Christian writing began with the letters of Paul, within a couple of decades of the crucifixion of Jesus, that is, in the 50s CE.” The second phase of Christian writings, the Gospels, were written in the latter half of the first century CE from “memories passed down by word of mouth, and perhaps sometimes jotted down in informal documents”. The end of the first and the beginning of the second century CE saw the third phase of the New Testament, which included “a diverse collection of Christian documents”.

But the dating is controversial, leading scholars to argue about the status of the Bible: conservatives emphasize earlier dates and ‘divine inspiration’; liberals, later dates and human inspiration. Sounds familiar, eh?

Scenes from the Passion of Christ by Hans Memling

The Bible’s theme. Jews’ reading of the Old Testament is as a form of instruction in how to live a good life on this earth; Christians’ reading of the Bible—Old & New Testaments—is as a form of instruction in how to gain life everlasting after death. “There is no before and after in Scripture,” according to an important rabbinic maxim, whereas Scripture is the story of man’s fall, redemption by Jesus, and man’s path to everlasting life, according to Christianity. But both start from “…there is only one God, who is the creator of everything”.

“The Bible tells us…’things we cannot tell ourselves’, in other words there are ideas and lines of thought in the Bible that it would be surprising for unaided human reflection to have arrived at.”

For that reason alone, reading the Bible is an utterly worthwhile endeavour.