…a continuation from Blog Number 44, July 2019

Why read fiction?

“…to help us better understand human nature in its most glorious and wicked forms. That is the experience no one can appropriate because it is the one we all share—regardless of our racial, ethnic, religious, national, or socioeconomic backgrounds.” (“The Confessions of Jeanine Cummins” by Christine Rosen, Commentary, March 2020) Thus, to pander to identity politics is to destroy literature itself. And that would be a tragedy for our common human identity.

Unfortunately, many publishers do pander to the identity cultists, making it much more difficult to find the good stories in the endless whine that passes for insightful writing and wins the literary prizes. So I avoid prize winners and look for new authors not fawned over by academia and the cognoscenti, with their novels often printed by small presses. Then there are always the old authors who have stood the test of time, who will give me hours of pleasure with a good story well told.

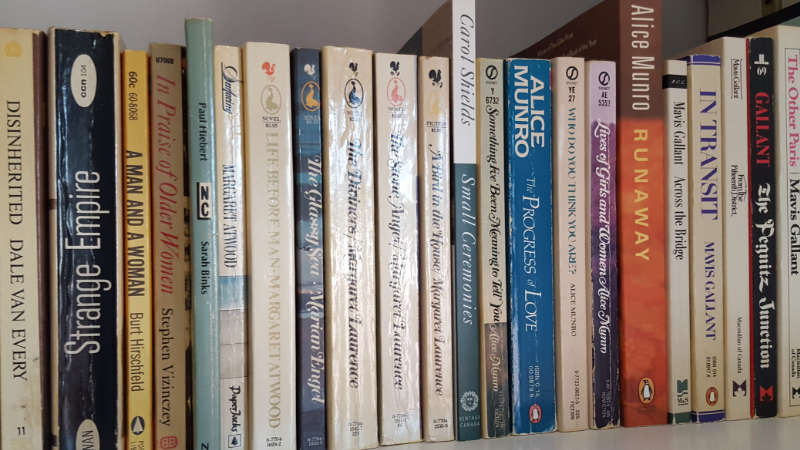

The Canadians

Mavis Gallant was born in Montreal, but moved to Paris as a young woman to write fiction fulltime. Determined to make a living doing what she loved, she took the leap into independence and maintained that independence for the rest of her long life. In her elegant, sometimes austere stories, Gallant can capture so much of a character with just one sentence, as she does first Mathilde, then Theo in Scarves, Beads, Sandals:

Mavis Gallant was born in Montreal, but moved to Paris as a young woman to write fiction fulltime. Determined to make a living doing what she loved, she took the leap into independence and maintained that independence for the rest of her long life. In her elegant, sometimes austere stories, Gallant can capture so much of a character with just one sentence, as she does first Mathilde, then Theo in Scarves, Beads, Sandals:

“She belonged to a generation of women who showed a lot of leg and kept life smooth, tight-fitting, close-woven.”

“His life was simple then, had grown simpler now. The seasons mean nothing, except that green strawberries followed by red. Weather means crossing the yard bareheaded or covered up.”

And she leaves endings ambiguous, like life.

First, I read the individual books: Across the Bridge, The Pegnitz Junction, From the Fifteenth District, In Transit, The Other Paris. Then, I read many of them again along with dozens of others in The Selected Stories of Mavis Gallant. When I read her stories, I had been to Paris only once; my sister and I drove into the city on Bastille Day in 1964 to be engulfed in the throngs of people making merry on the boulevards, in the cafes, in the parks, everywhere in this exotic French city. Some 30 years later in the 1990s, Jack and I visited Paris often to see our son; during the day while he was at work, we walked for miles and miles on the narrow streets and wide boulevards, becoming not familiar, but comfortably awed and fascinated by Parisians at home. So perhaps I’ll return one of these shut-in afternoons to Gallant’s stories to see the city again, this time through the lens of time and experience.

Alice Munro is the next on the shelf, our very own Nobel Prize in Literature winner in 2013. She, like Gallant, wrote mainly short stories, with the focus squarely on the female point of view from girlhood to young womanhood to adult womanhood to old womanhood. I started with Lives of Girls and Women and marched on through Who Do You Think You Are?, Something I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You, The Progress of Love and Runaway. Munro’s world is small-town/rural Ontario, which shares many characteristics with my childhood of living on a farm and going to school in a small town on the Prairies.

And I read her because:

“People’s lives, in Jubilee as elsewhere, were dull, simple, amazing and unfathomable—deep caves paved with kitchen linoleum.”

She was “voracious” in wanting “to write things down”, making lists “of all the stores and businesses going up and down the main street and who owned them, a list of family names…” and on and on.

“And no list could hold what I wanted, for what I wanted was every last thing, every layer of speech and thought, stroke of light on bark or walls, every smell, pothole, pain, crack, delusion, held still and held together—radiant, everlasting.” (“Epilogue: The Photographer”, Lives of Girls and Women)

And I continue to marvel at the ‘dull, simple, amazing and unfathomable’ lives of people all around me all over the world.

Margaret Laurence was a generation older than me, but her childhood was closest to mine, both in kind and location: the small town of Neepawa, Manitoba, about 200 km southeast of our farm. Her Manawaka cycle (with Manawaka based on Neepawa) of novels and short stories—The Stone Angel, A Jest of God, The Fire-Dwellers, The Diviners and A Bird in the House—mirrors much in my childhood and teenage years. Her female characters are evocative of the mothers and teachers who dominated the homes and schools of 1940s and ’50s Prairie life.

This cycle tells the story of strong women struggling to be their own women in the often harsh climate of Prairie weather and social structures. Hagar Shipley, the central character in The Stone Angel, has an uncanny resemblance to my mother: admirably determined to keep our large family fed and together in the face of madness and long, lean winters, but distressingly stubborn in refusing to reward her oldest son’s pivotal role in the farm’s survival by only ceding some ownership when forced to. Hagar/Mom provokes admiration, but love only grudgingly.

The other Margaret, Margaret Atwood, intrigued me with her debut novels, The Edible Woman and Surfacing. I read them shortly after they were published in the early 1970s, and was impressed by Atwood’s fluent storytelling. The first explored a young woman’s growing aversion to food, an affliction that was just emerging into the public consciousness. It ended triumphantly, with the heroine baking, then eating a cake in her image—a very satisfactory ending! Having come from a background where everyone had to work hard to plant, nurture, harvest and cook the food on one’s plate, I find the concept of refusing food foreign, indulged in by rich, pampered girls. The second is a very Canadian exploration for the heroine’s father, who has disappeared in the wilds of Ontario, a little pretentious, but interesting.

I kept reading Atwood’s novels as they were published, a little out of obligation because she’s such a Canadian icon and I should like her, n’est-ce pas? Then The Handmaid’s Tale came out and was showered with praise. I read it and felt betrayed. The setting is incredible, that is, it cannot be believed. She has a female dystopia staring her in the face in many Islamic lands, where women truly are second-class citizens at best and chattel often. Or she could have created an imaginary dystopia as so many of her contemporary novelists are doing. But, no, she had to indulge the kneejerk anti-Americanism of so many of her Greater Toronto Area neighbours, and that ended my attention to Ms. Atwood in all her pontificating venues.

Life’s too short to pay attention to false prophets.

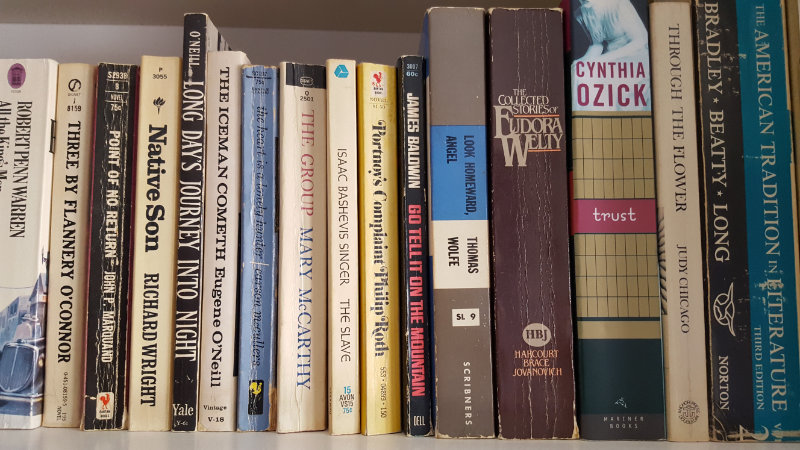

The Americans

Like the vast and varied land itself, American literature spans the gamut, from blacks and whites and everyone in between, from rich and poor and every status in between, from urban and rural and every place in between. Many of my favourites hail from the South, exploring the intricate relations between blacks and whites at all levels of the social ladder. Some giants on the writing scene are:

- Flannery O’Connor, whose short stories set in the south subtly reveal the characters through dialogue and dialect. She never uses a broad brush to paint a whole person or a whole group as black or white in the humanity stakes, but creates individuals, each with his or her idiosyncrasies intact.

- Richard Wright, whose Native Son was my introduction to the world viewed through a black man’s eyes with its shocking action and refusal to repent by Bigger Thomas. With the novel’s publication in 1940, Wright ripped the cover off racial oppression and forced white Americans to see and begin to redress this legacy.

- Eugene O’Neill, whose plays show anger and pathos in equal measure. And they are long; we went to an afternoon’s performance of Long Day’s Journey into Night in London’s West End, with Jessica Lange playing the mother, and came out 3½ hours later drained, but exhilarated by this raw portrayal of family in all its gaudy dysfunction and function.

- Carson McCullers, whose The Heart is a Lonely Hunter with its sadness and loneliness in the heart of us as we struggle to connect to others. But this loneliness is even more profound for people with disabilities, in this case deaf-mutes, and their struggle to allay their loneliness continued to haunt me long after I read the book. (I think its title ranks right up there with By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept in the best-title category!)

- Mary McCarthy, whose The Group inspired me to create a group of four couples who met regularly, now irregularly, to eat and drink and talk of many things. As so many couples nowadays, two have changed, but two have stayed the same to anchor the memories as we all grow old together. And of course, I will always remember McCarthy for her summation of Lillian Hellman, a contemporary writer in the same New York milieu, “Every word she writes is a lie, including ‘and’ and ‘the’.” Writers’ disputes are delicious!

- James Baldwin, whose Go Tell It on the Mountain was a semiautobiographical novel portraying his, and blacks’, treatment in mid-20th-century America. Like Richard Wright’s work, it uncovered the simmering anger of black artists and leaders at the overt and covert prejudice pervading the US; unlike Wright, who saw the opportunity of America, Baldwin rejected it completely and moved to France to live for most of his life. I remember being impressed by his experience as a black, gay man in a time and place when both presented huge barriers to living a full life in American society. But I also remember being disappointed that he blamed others for everything and accepted none for himself, even when his character flaws were on full display. Having said that, I highly recommend it as a powerful chronicle of blacks in 1950s America.

- Thomas Wolfe, whose Look Homeward, Angel I devoured when I read it in my early 20s. It is romantic and wondrous and sprawling and sad, a story of a young man coming of age in provincial America, and I was enthralled from the very first page, racing through the remaining 500+ pages as if my life depended on it.

“Each of us is all the sums he has not counted: subtract us into nakedness and night again, and you shall see begin in Crete four thousand years ago the love that ended yesterday in Texas. … Each moment is the fruit of forty thousand years. The minute-winning days, like flies, buzz home to death, and every moment is a window on all time.”

Superb! - Cynthia Ozick, whose Trust, her first novel, starts with the narrator’s graduation from college when she begins to try to find her father, Gustave Nicholas Tilbury. He is a shadowy free spirit she knows almost nothing about, but now she wants to meet him, and he wants something from her. The story is interesting, full of odd people, funny things and bizarre events, but its incoherence and the narrator’s offhand reactions are offputting at times. I intended to read more of Ozick after reading this slab of a novel, but I never did. Perhaps I will…Heir to the Glimmering World sounds intriguing…

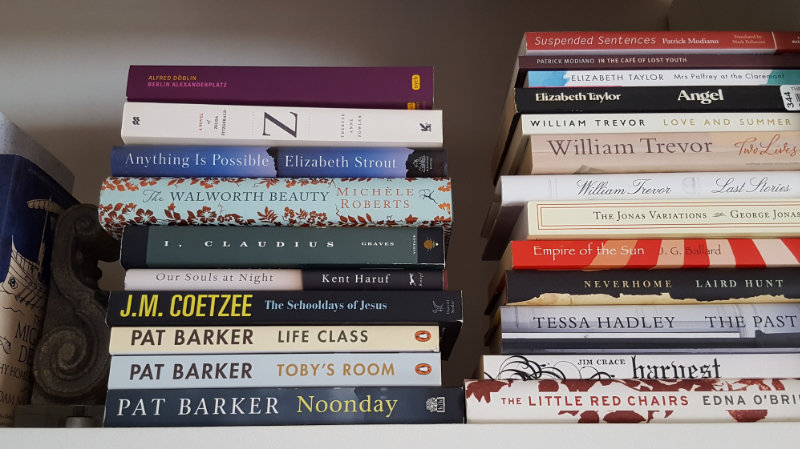

The Brits

When I read British authors, I feel like I’ve come home. At least to my imaginary home where living in a rickety, rambling old house offers adventures around every corner in the company of eccentric, but mainly benevolent people and creatures. The Brits consume hours and hours of my reading time—but still less rapacious than with our TV viewing hours!—and consist of multitudes. But in this ramble, I’ll talk about only two and leave the others for other blogs.

I discovered Elizabeth Taylor (the writer, not the actress) not long ago, even though she was born in 1912 and published her first novel in 1945. Like John Williams, she’s not widely known; like John Williams, her writing is superb! I found her on my usual path of reading column yards of reviews in one of my magazines. Her novel Angel (1957) has Angelica Deverell as the heroine, a “less than lovely daughter” in face and personality of a poor, but respectable widow, who fancies herself a writer. She churns out tawdry romances, and keeps truth at bay—a “kind of a Madame Bovary with a pen”. When she is “menaced by intimations of the truth”, she’s “learning to triumph over reality” until “the truth was beginning to leave her in peace”. Echoes of Madame Bovary, indeed! (Which I just reread in Collingwood in January, and wrote about in Blog Number 48.)

Angel would sooner live the life of her torrid romances—a world of white gloves and tea and flirtation, stopping at the bedroom door—than the real life of love and sex. The contrast of the suggested purple of her prose to Taylor’s lucid telling of Angel’s story is delightful. But the reader has to grudgingly admire Angel: She is determined to create a comfortable life in spite of being born on a lowly rung of class-ridden Britain’s social ladder and of being blessed with neither beauty nor talent. Angel has grit.

Mrs. Palfrey, on the other hand, is an altogether appealing character in Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont. Laura Palfrey is the widow of a colonial administrator and mother of one daughter, who lives in Scotland, and a grandson, who lives in London and works at the British Museum. In straitened circumstances, as so many women are in their retiring years, she moves into the Claremont, a modest hotel modestly priced. When she arrives in a taxi on a rainy afternoon, her spirits rise when she sees “laurels in the window When she arrives in a taxi on a rainy afternoon, her spirits rise when she sees “laurels in the window boxes; clean curtains—a front of emphatic respectability”. Then her heart sinks when she’s in her room: “she thought that prisoners must feel as she did now, the first time they enter their cell, first turning to the window, then facing about to stare at the closed door”. But being a redoubtable woman, she soon overcomes her “black mood” and accepts her new life.

“As she waited for prunes, Mrs Palfrey considered the day ahead. The morning was to be filled in quite nicely; but the afternoon and evening made a long stretch.” And there you have it: old age described when you are no longer needed. (For younger generations, our current pandemic has opened a window of empathy into the often deadly boredom of retirement.) But her character won’t allow self-pity, so when asked by another of the “ranks of the rejected” if she has any relations in London, she says, “My grandson lives in Hampstead,” and doesn’t disagree when Mrs Post says the grandson will probably be visiting her often. He doesn’t. And then one day, Mrs Palfrey meets the handsome young writer Ludo, gets caught up in the lie that he is her grandson, and an unlikely and interesting friendship is formed.

Delightful, and the reader cheers for Mrs Palfrey!

I had read about J.G. Ballard when he was first published in the 1960s, but his futuristic themes of dystopian nightmares held no appeal for me. Then in 2015, I picked up Empire of the Sun and was mesmerized. In the Foreword, Ballard writes, the book “describes my experiences in Shanghai, China, during the Second World War, and in Lunghua C.A.C (Civilian Assembly Centre), where I was interned from 1942 to 1945”. But he calls it a novel, and I think he does this to give himself licence to present his eyewitness account more dramatically and coherently without having to slow the story with the often tedious and incoherent minutia of everyday.

Whatever the reason, the reader is plunged immediately into the terror of war when young Jim is separated from his parents in the chaos of the Japanese occupation of Shanghai. Then the reader embarks on Jim’s adventure in survival as he navigates the nightmare of Shanghai’s transformation from the city of his privileged boyhood to a merciless martial city, and then the daily horror of the concentration camp as the Japanese obliterate any trace of his former life.

Ballard’s writing is brilliant, unsparing in its descriptions of the cruelty and then lit with the odd note of grace. Jim’s coming-of-age story—from a well-off family living a privileged ex-pat life to the tattered world of post-WWII—is timely for today’s privileged youth: What will the world look like after the Covid-19?

Until the next ramble through my bookshelves…

This time again, I think I’m done. But probably not yet.

Because there is still a discussion of God and values, with the books by C.S. Lewis, A.N. Wilson and John Barton leading the way.

Maybe next time…

This is truly turning into a lifetime project!

(And maybe I’ll even entice my grandchildren to come and take whatever books they desire from my bookshelves to fill the shelves of their beginning libraries.)